The treatment

In this

view, the benevolent handling of Germany

In reality, history shows that story -- understandably popular in the Anglo-Saxon world, particularly the

English Keynesian side of it -- to be inaccurate. Elites’ enlightenment counted for little.

----------

In many

respects Henry Morgenthau, Jr. (1891-1967) seemed an American version of the

Keynesian enlightened bourgeois/intelligentsia: an architect by training, Morgenthau

came from an influential patrician family of New York Turkey

As

Secretary of the Treasury in the Roosevelt Administration since 1934,

Morgenthau -- although himself sceptical of Keynesian ideas -- had played a

pivotal role in shaping the New Deal, and exerted considerable, if informal and

contested, authority in the wartime direction of economic effort of the U.S.

With their

Soviet “frenemies” bearing the brunt of the cost, human and material, and

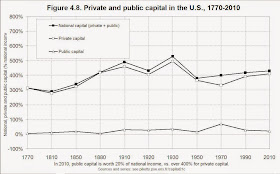

American capital (in Thomas Piketty’s definition) emerging largely unscathed

after 40 years turmoil, by 1944 those efforts started to bear fruit: the tide

of history turned decidedly against the Axis. It was time for a resurgent U.S.

|

| source: Piketty, Thomas. "Capital in the 21st Century", chapter 4. |

|

| source: Piketty, Thomas. "Capital in the 21st Century", chapter 3. |

During this

time, following Steven (2005), a new lobby formed in the U.S. advocating a “harsh peace” with Germany

With that agenda in mind, during the September 1944 Second Quebec Germany

Quoted by

Moggridge (1995), Morgenthau describes PM Churchill’s initial reaction to a previous

private presentation:

"After I finished my piece he turned on the full blood of his rhetoric, sarcasm and violence. He looked on the Treasury plan, he said, as he would on chaining himself to a dead German.

"He was slumped in his chair, his language biting, his flow incessant, his manner merciless. I have never had such a verbal lashing in my life."

For all that outburst, however, Churchill acquiesced to the plan, as it was supported by

Morgenthau’s boss. After all, already in the January 1943 Casablanca Conference Churchill had been forced to accept publicly embarrassing impositions

from Roosevelt, of whom Churchill would meekly admit: “I was his [i.e. Roosevelt ’s] ardent lieutenant".

Worse was in

store for Morgenthau. To his chagrin, the leaked proposal was

badly received by most of the press, public opinion, and sectional interests

inside the Administration (particularly the Department of War and the State

Department, headed by more conservative, pro-business, politicians).

The Nazi

propaganda machine, too, was quick to take full advantage of it. Lt. Colonel

John Boettiger, Roosevelt 's son-in-law, has

been quoted to the effect that the propaganda afforded to the Nazis was "worth

thirty divisions to the Germans."

Faced with an

overwhelmingly adverse reaction, the proposal was swiftly removed from public

discussion. In October 1944, Roosevelt personally denied there ever was any such

plan, in spite of which, by May 1945 Harry Truman (whom succeeded Roosevelt

after the latter’s death in April) accepted the Joint Chiefs of Staff directive

1067.

Morgenthau,

whom Truman would sack in July 1945, has been quoted as saying that he hoped "someone

doesn't recognize it [i.e. JCS 1067] as the Morgenthau Plan."

----------

After two

years occupation, beginning the Cold War, Truman dispatched former U.S. president Herbert C. Hoover to Germany and Austria Hoover

“There is the illusion that the new Germany left after the annexations can be reduced to a 'pastoral state'. It cannot be done unless we exterminate or move 25,000,000 people out of it.” (here)

"The Marshall Plan … is not a philanthropic enterprise … It is based on our views of the requirements of American security … This is the only peaceful avenue now open to us which may answer the communist challenge to our way of life and our national security." (here)

Perhaps clearer

and more to the point were the words of general Lucius D. Clay, head of the Office of Military Government, United States:

"There is no choice between being a communist on 1,500 calories a day and a believer in democracy on a thousand". (here)

(to be continued)

Related:

Stuttering George and Amnesia. Feb. 2, 2011.

References

Casey, S. (2005). The Campaign

to Sell a Harsh Peace for Germany

to the American Public, 1944-1948. History, 90(297), pp.62-92.

Moggridge, D. (1995). Maynard Keynes. London: Routledge. p. 772.

No comments:

Post a Comment