"By birth, Socrates belonged to the lowest class: Socrates was rabble[*]. We are told, and can see in sculptures of him, how ugly he was. But ugliness, in itself an objection, is among the Greeks almost a refutation. Was Socrates a Greek at all? Ugliness is often enough the expression of a development that has been crossed, thwarted in some way. Or it appears as declining development. The anthropological criminologists tell us that the typical criminal is ugly: monstrum in fronte, monstrum in animo [monstrous in appearance, monstrous in spirit]. But the criminal is a decadent. Was Socrates a typical criminal? At least that would be consistent with the famous judgment of the physiognomist that so offended the friends of Socrates. This foreigner told Socrates to his face that he was a monstrum - that he harbored in himself all the worst vices and appetites. And Socrates merely answered: 'You know me, sir!'

"Socrates' decadence is suggested not only by the admitted wantonness and anarchy of his instincts, but also by the overdevelopment of his logical ability and his characteristic thwarted sarcasm. Nor should we forget those auditory hallucinations which, as 'the daimonion of Socrates,' have been given a religious interpretation. Everything about Socrates is exaggerated, buffo, a caricature; everything is at the same time concealed, ulterior, underground." (Emphasis added. see here)

The author of that extraordinarily vile invective against Socrates became influential during the twentieth century, after a lifetime of obscurity and mediocrity: Friedrich Nietzsche.

What did Socrates, largely a mythical figure, do to deserve that outburst? "

What really happened there"?

Credited by Plato, his disciple, with being the first true philosopher, little is known with any certainty about Socrates. Rightly or not, he emerges from Plato's writings as a rationalist, whose dialectical method was based on logical argument.

One could interpret Nietzsche's venom and slander as the words of a depraved Don Quixote, tilting at windmills, and leave things at that.

My reading, however, is different. Nietzsche's bile, directed against his view of Socrates, the man, should be interpreted as a hateful tirade against what Socrates came to represent:

"With Socrates, Greek taste changes in favor of logical argument. What really happened there? Above all, a noble taste is vanquished; with dialectics the plebs come to the top. Before Socrates, argumentative conversation was repudiated in good society: it was considered bad manners, compromising. The young were warned against it. Furthermore, any presentation of one's motives was distrusted. Honest things, like honest men, do not have to explain themselves so openly. What must first be proved is worth little. Wherever authority still forms part of good bearing, where one does not give reasons but commands, the logician is a kind of buffoon: one laughs at him, one does not take him seriously. Socrates was the buffoon who got himself taken seriously: what really happened there?" (Emphasis added)

In Nietzsche's mind, Socrates morphs from risible "

buffoon" into a fearsome threat, because by adopting reason and dialogue, embodied by Socrates, the true Greeks of "

noble taste" and "

good bearing", the "

good society", allegedly forfeited their "

authority", their "

command": "

the plebs come to the top".

Recognizing implicitly the weakness of his position, Nietzsche gives up on rational reasoning, and, instead, appeals to an hominem argument (nominally against the man, but by association, against the ideas of the Enlightenment); in so doing expresses without masks the fear that others also expressed in

barely disguised form (Corey Robin called that "

elective affinity").

And, to Nietzsche's horror, since the Enlightenment, reason and democracy were predicated as the way of the future for Europe and the world.

Indeed, a spectre was haunting Europe.

----------

Nietzsche's fears about reason were as premature and unjustified as his attack is full of ironies: democratic dialogue between reasonable and polite gentlemen

does not lead to social change.

That, however, does not stop Nietzsche from fearing the mere possibility. This makes of him a rightful enemy of democracy and a prophet of fascism, in addition to being a Post-Modern precursor. Is in this sense that Nietzsche deserves to be read and where he does provide insight.

----------

Ironically, the man who distrusted science and reason, appealed to

Cesare Lombroso (the father of the "science" of anthropological criminology) to justify his tirade.

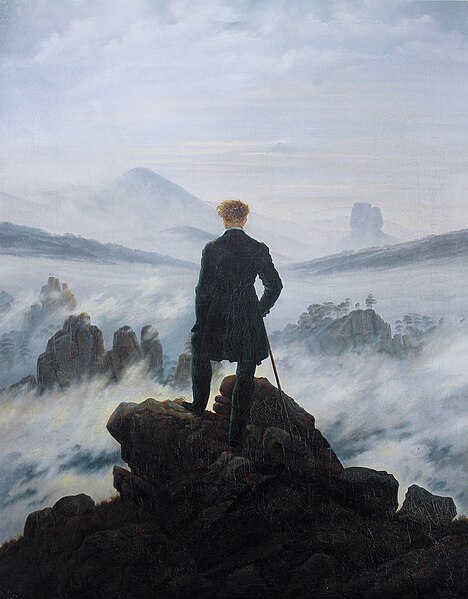

After mercilessly mocking Socrates' alleged ugliness, Nietzsche ended up looking like this:

|

| Portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche by Hans Olde (1899/1900) [A] |

And after throwing stones on Socrates' reason roof, fearing reason all his life, only at the end Nietzsche fully embraced unreason [#]:

"To his friend Meta von Salis he [i.e. Nietzsche] wrote:

" 'God is on the earth. Don't you see how all the heavens are rejoicing? I have just seized possession of my kingdom, I've thrown the Pope in prison, and I'm having Wilhelm, Bismarck, and [anti-Semitic politician Adolf] Stocker shot.'

"To his closest friend, theologian Franz Overbeck, Nietzsche wrote:

" 'The world will be turned on its head for the next few years: since the old God has abdicated, I will be ruling the world from now on'."

There is poetic justice in that.

Notes:

[*] The original in

German reads "

Sokrates gehörte, seiner Herkunft nach, zum niedersten Volk: Sokrates war Pöbel". The noun "Pöbel" translates as "rabble" and it is this word I use, instead of the softer adjective "plebeian", which Walter Kaufmann and R.J. Hollingdale used. While etymologically connected to plebe, Pöbel carries in German a stronger negative connotation than the English plebe.

[#] Quoted from Sax, Leonard. What was the cause of Nietzsche’s dementia?

Journal of Medical Biography 2003; 11: 47–54.

Image Credits:

[A] "Portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche by Hans Olde (1899/1900)". This image is in the

public domain because its copyright has expired. Source:

Wikipedia.