|

| The two faces of Janus. [A] |

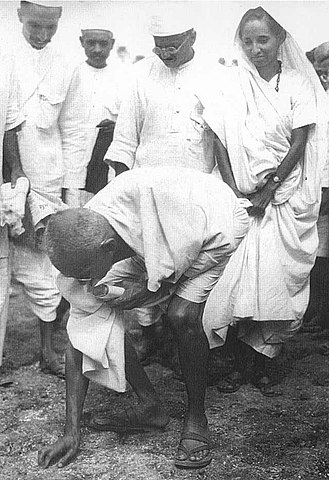

Standing on the shores of the Arabian Sea, Mahatma (the Great-Souled) Gandhi collected a muddy lump of salt from a salt pan. Then, as he raised his hand for all to see, he proclaimed triumphantly: “With this, I am shaking the foundations of the British Empire.”

Absurd as it may seem, that is exactly what he did. Some seventeen years later, the Raj collapsed and the British quit India. Gandhi’s deceptively simple act snowballed and inspired millions all over India.

Why?

----------

To Winston Churchill, in the early 1930s, Gandhi looked like a half-naked fakir. Today commentators in the English-speaking world regard Gandhi more favorably, as a kind of prophet straight out from the Bible.

|

| Gandhi collecting salt from the beach.[B] |

Superficially opposed, both assessments are similar: they privilege appearances over reality.

During their rule of India, the British held a monopoly on salt. Laws had been enacted declaring the extraction, production and sale of salt by natives unlawful. Only the British were allowed those activities.

Whatever else he was, Mohandas K. Gandhi was astute; he also was a lawyer, from University College, London. As a lawyer, Gandhi knew that the words “lawful” and “just” are not synonymous. For the British their lawful monopoly was extremely profitable; for the Indians, it was deeply unjust. The Salt Laws made an unjust practice lawful; by extension, the laws themselves were unjust.

He also knew that human laws, unlike natural laws, are the creation of humans. There’s nothing we can do about natural laws, even if unjust, but we don’t need to suffer unjust human laws. If the British enacted the Salt Laws, they could repeal them. Before leaving for Dandi, he wrote the British Viceroy demanding precisely that on behalf of all Indians. Given a chance to do something, the Viceroy – no doubt with encouragement of opinion-makers at home – chose to do nothing.

It was up to the Indians then. When Gandhi, the lawyer, picked up that lump of salt, he knew he was breaking the law. He made no secret of that; evidence was abundant (see the photo above). He, furthermore, assumed responsibility for his action and was arrested, making no attempt to resist.

Civil disobedience against unjust laws is meant to be peaceful. But the colonial police were not as restrained. This, however, only strengthened Gandhi and his followers: it highlighted the injustice the protesters were protesting against.

----------

But why did the Viceroy make such a fuss about something as trivial as salt? Why didn’t he just get the damned Salt Laws repealed?

Because salt wasn’t trivial at all. British colonial domination of India was built upon unjust laws. To put this differently, it wasn’t the Salt Laws that made the Raj unjust, it was the Raj that required unjust laws. To repeal the Salt Laws alone wouldn’t have changed that.

The Viceroy found himself in the same position Hong Kong’s Carrie Lam would find herself some ninety years later: after one demand is accepted, others would follow until the whole building crumbles.

Nowadays, those who see Gandhi as a messianic figure would never dare to utter the words “sedition” and “subversion” in a sentence, next to his hallowed name. Churchill was bolder. Although what people most remember is his “half-naked fakir” malicious putdown, he also called Gandhi “seditious lawyer”. Of the two descriptions, the second is the more relevant and perceptive: Gandhi was indeed a subversive. A peaceful and highly moral one, subverting an unjust order. Believe it or not.

----------

Known as the Salt March, that episode is a prime example of civil disobedience, but there are many others.

Meet Peter Hartcher, international and political editor of The Sydney Morning Herald.

As international editor, no doubt he’s heard about Gandhi, although he may have forgotten the particulars. And he’s written about the 2019-2020 Hong Kong protests, showing himself deeply sympathetic to anti-CCP Hongkongers

The protests started out as a textbook example of civil disobedience, protesting peacefully against a notorious extradition to China bill. Protesters opposed that bill because they considered it unjust; faced with a Legislature rubber-stamping whatever Beijing presented, civil disobedience was not only morally justified but the only realistic option, even if local authorities declared it – as they repeatedly did – unlawful.

Soon, however, the protests became more violent. That’s when Hartcher decided to remind protesters of Gandhi’s example. He also advised them – wisely, in my opinion – not to place too much faith on foreign help, particularly that of Donald Trump.

Commenting on events thousands of kilometres away, international editor Hartcher is all admiration, understanding, reasonableness, even solidarity and comradeship – almost revolutionary, I dare say. Protesters in Hong Kong didn’t use the words “sedition” and “subversion”, but that’s precisely what they were doing (as Hong Kong authorities knew well) and if one agrees with the protests, “sedition” and “subversion” were just, even if unlawful.

----------

The moment Hartcher takes off his international editor cap and puts on his domestic politics editor cap, commenting on Australiam affairs, things change. No more sympathy, solidarity or admiration.

Don’t believe me? Check this out. Hartcher quotes Sally McManus:

“I believe in the rule of law when the law is fair and the law is right. But when it’s unjust I don’t think there’s a problem with breaking it.”

But in this piece Hartcher makes no reference to Gandhi. In other places laws can be unjust. Not so in Australia, where all laws, by the fact of being laws, are just and if they were enacted by Labor, then only creatures as twisted as workers can disagree with those laws. Civil disobedience, which Hartcher recommends Hongkongers, is out of bounds for Australian workers.

More sober – or less imaginative – than Churchill, Hartcher somehow avoided calling McManus “half-naked fakir”. Instead he used the formulaic “militant”, which for those like him is the most terrible sin. To gain their approval unions must be the opposite of militant: apathetic, restrained, passive, conformist.

While Hongkongers are brave, McManus and the union movement are – in Hartcher’s opinion – shrills: dogmatic, retrograde, power-hungry and thuggish (another all-time favourite of Australian bosses).

I wouldn’t be surprised CCP propagandists described Hong Kong protesters in terms not unlike those Hartcher used to describe Australian workers.

So what were McManus’ demands? Here’s one, in Hartcher’s own words: “banning outright any enterprise agreements that are agreed without a union”. You see, Aldi treat their staff well without the need for pesky union representation – or so he writes. Therefore, no unions are needed.

A second example: ACTU wants a return to the “old system of negotiating workplace agreements to apply across an entire industry”. This, Hartcher writes, would force “smaller or struggling companies” pay their staff the same “big, profitable companies” pay their staff. So, to make him happy, workers employed by struggling companies need to subsidise their employers until they are big and profitable, at which point employers – full of gratitude – will spontaneously raise their wages and improve their working conditions, presumably like Aldi allegedly does. That sounds a lot like the Seven-11 model of flexibilty. You see, employers need flexibility more than workers deserve adequate pay and working conditions – at least for Peter Hartcher, political editor – and his wrath will fall upon anyone saying otherwise.

----------

Amazing how the same person can go from the moderately thoughtful to the outright ignorant and puerile, as soon as workers’ rights are involved. It makes one believe in split personalities.

Image Credits:

[A] Ultima Thule, 1927. Image in the public domain. Source: Wikipedia.

No comments:

Post a Comment